Rock, Paper, Scissors, Shoot!

INTRO

For my first build post I’d like to share a project from earlier this semester—a robotic hand that plays Rock, Paper, Scissors, jokingly yet appropriately named the Handroid.

In order to gain entry to the McGill Robotics Team, every potential member must go through a tryout process. In this process, prospective members are placed into randomly selected teams of 6 or 7 and are tasked with completing a “Mini-Project” in three weeks time. The only restriction or guideline was that each team must construct a robot that plays a game.

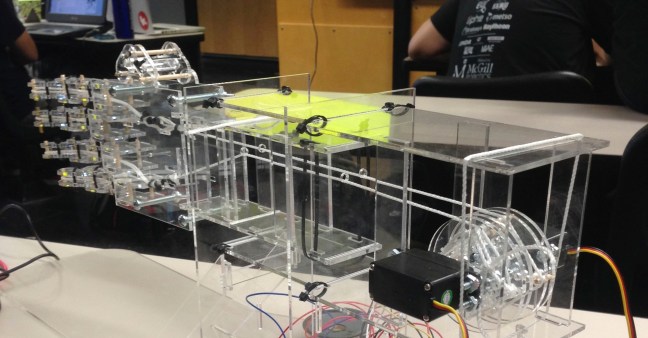

My team quickly settled on making an Rock, Paper, Scissors robot that would be able to play against people in real time. The project was divided up into three components: the mechanical system, the software “brain” component, and the interface between the two, the microcontroller. I was in charge of the design and fabrication of the mechanical system.

BUILD

I spent a lot of time staring at my own hands. Watching how they worked. What shapes my muscles could pull my fingers into and what shapes they couldn’t. Though I’m by no means the first person to make this decision, I came to the conclusion that a tendon-based system would be the simplest and most effective way to simulate lifelike motion.

The hand was modeled off of measurements from my own right hand, and operated more or less in the same manner. The mechanism for bending was quite simple: a pliable, springy band (braided steel wire) down the back, and a tendon (string) down the inside. When the string is tensioned, the finger curls up. When the tension is released, the braided steel wire bends the finger back into straight shape.

It consists of six different materials:

- 3mm lasercut acrylic

- String (tendons)

- Wooden dowels (joint hinges)

- Braided steel wire

- Zip-ties

- Various nuts and bolts

RPS is a very basic game. There are three moves: no fingers (rock), two fingers (scissors), four fingers (paper). Given this fact, the hand was configured to be driven by two motors. The underactuated design greatly simplified the control aspect of the robot. Pairing together the pointer, middle fingers and the ring, pinky fingers was as easy as tying the tendons (strings) together. The thumb stood idle.

Once the fingers were operational, the hand needed a stand. A quick design session and lasercut later, and it had its very own rickety base. I’m not a huge fan of glue, and I like to challenge myself when designing lasercut parts by attempting to make them fit together with as few fasteners as possible. Some designs work out better than others. This stand was by no means robust, but it got the job done.

Meanwhile, the guys on the software side had been doing some great work with computer vision. Using a DIY greenscreen, a large database of different hands in rock/paper/scissors formations, a webcam, and the OpenCV library (very cool—if you have some programming experience and are interested in computer vision, I’d highly recommend checking it out), they created a system that could accurately read the other player’s throw roughly 90% of the time. Using this data, the hand would then throw the opposite move, beating the human player every time. Yes, it’s cheating. That’s what makes it fun.

FINAL PRODUCT

Here’s a video of the end product. In this video it’s playing against somebody who’s never played it before—which shows in that the human has a tough time following the rhythm the robot sets. I wish I had a better video demonstration, but in the rush of the whole project this was the only one I ended up taking.

Against somebody who knows what he’s doing and follows the proper rhythm, the hand can read your move and decide what to throw in as little as half of a second. At its fastest, it’s almost quick enough to be convincing, but most of the time it’s pretty clear that the robot is cheating.

TAKEAWAY

At first, I was less than pleased to find out that I would yet again be on the short end of the tryout stick. Once it was all said and done, however, I came to realize that it was a good way to start the year off with the robotics team. Being able to build a project from the ground up in a short amount of time, to work with almost no restrictions, and to design parts one night and lasercut them the next really got me in the rapid design and prototyping mindset. Getting the juices flowing this way has helped me speed up my conceptual design process, and is proving very useful in the planning stages of larger projects, like the Mars rover I’m working on with the team for competition in the Mars Society’s 2015 University Rover Challenge.

On the mechanical design side, there were a few important takeaways. They’re listed as follows in no particular order:

- You can get a lot done with purely planar components.

- Conceptual design is arguably the most important part of any project. Entering the CAD phase without having any idea what the final product will look like is a recipe for disaster. Also a massive headache.

Rough conceptual sketch rendered in Blender 3D. - Sketching isn’t limited to pen and paper. For more complex, 3D projects I prefer to do my initial, very basic sketches on paper and then move in to Blender 3D to flesh out the design further. For those of you that don’t know, Blender 3D is an open-source 3D graphics rendering program. As it is made for visual rendering, it has no real dimensions and sculpting is much, much smoother than in an engineering CAD program. After getting over the initial (read: steep) learning curve this summer, it is now a vital tool in my workflow from idea to final product.

- Zip-ties are your best friend. Well, I actually can’t speak for you, but they’re my best friend.

- Rounding up can lead to trouble. The Handroid was modeled off of precise measurements of my own hand, but after rounding each number up to the nearest multiple of 5 or 10mm, it ended up bulky and unnatural.

- Take pictures and videos along the whole build! Looking back, I realize that I don’t have many good pictures or videos, especially videos of it working at its best. Luckily, it’s still in one piece and the code still exists somewhere, but it’ll be a bit of a hassle to get it all back together if my teammates and I ever decide to.

All in all, I’m pretty happy with how it turned out. Three weeks is not a lot of time, especially with a full courseload and all of the other time consuming activities that come along with university life. I can’t thank my teammates enough—the mechanical side of this project was only one part, and they really blew me away with the quality and reliability of their software. I wish that I had played a bit bigger part in designing the brain, but in the end you only have so much time, and you need to prioritize. Maybe another day.

Well, this post got kind of out of hand. Pun intended. If you’ve made it this far, thanks for reading and stay tuned! There are updates on this project (there’s a lot of room for improvement here, and I intend to use it) on the way, as well as write-ups of different builds.

GH

One thought on “BUILD: Playing Rock, Paper, Scissors with a Cheating Robot”