Drainage Tower Defense: Learning the Unity Game Engine.

INTRO

If you’ve purchased any games from the App Store or Play Store in the past few years, odds are you’ve come across the Unity Game Engine. It’s become a heavyweight in free and light-commercial game development, and by no accident. It provides a stable and powerful base to build any game on, from first-person shooters to iOS puzzlers.

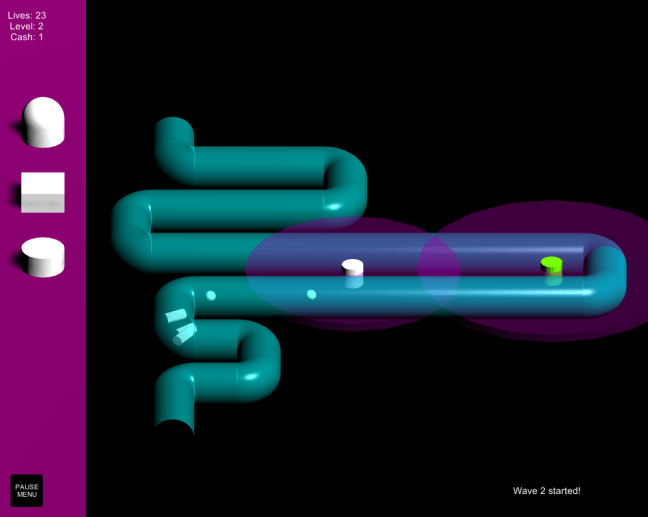

For this build, Unity was used to make a Tower Defense game. Introducing: Drainage TD.

BUILD

This game was a term project for my Software Engineering course. The aim of the course was to provide a comprehensive overview of software engineering best practices, including design patterns, modeling, testing, and system architecture. In order to demonstrate the principles taught in lecture, we were tasked with building our own Tower Defense games. The course was instructed in Java, and our games were also to be coded in Java. Anticipating the nightmare of making a game using Java’s Swing graphics library, my group was able to negotiate our way into using Unity and C# instead.

In most every case, C# and Java are indistinguishable. From the syntax to the polymorphic structures, the two languages operate in a largely identical manner. However, using the Unity Game Engine made things a tad more challenging.

Developing in Unity really means developing off of the base Unity class MonoBehaviour. Every script that is directly attached to a physical object, dependent on physical objects, or creates physical objects must extend this class. This is both a blessing and a curse, in that MonoBehaviour has various built-in methods such as Update(), Start(), OnClickEnter(), etc. that handle the unsavory task of setting up a game timer and clocked environment. However, this restricts all MonoBehaviour subclasses to fit this mold, which sometimes complicated matters surrounding inheritance.

After a little more than two weeks of intense development, the game was completed and ready for submission. In total, there are 35 classes and subclasses with about 3,000 lines of code—solidly making it my largest project.

DETAILS

Drainage is comprised of five different “scenes”: Main Menu, Map Builder, Gameplay, Game Over, and Victory. Here is a short overview of each:

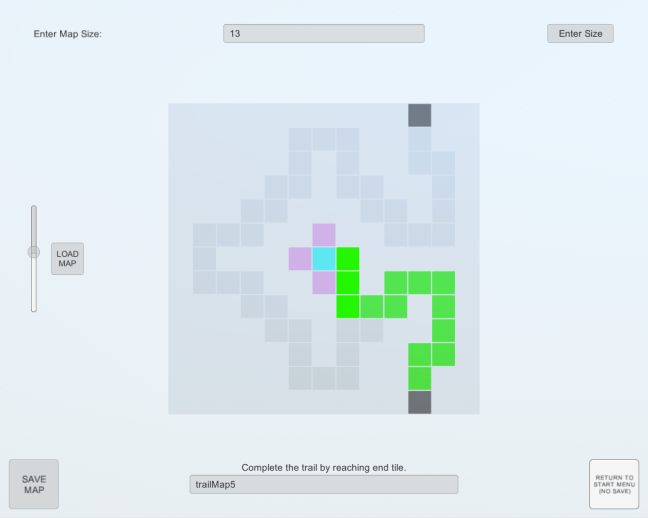

- Main Menu : Start screen that allows you to choose a map from the map list and launch a game, or launch into the Map Builder.

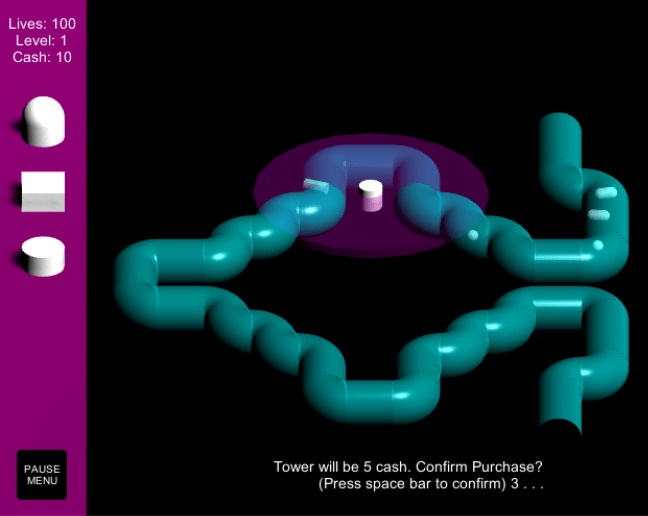

- Map Builder : Just how it sounds—make new maps of any size, or “edit” existing maps.

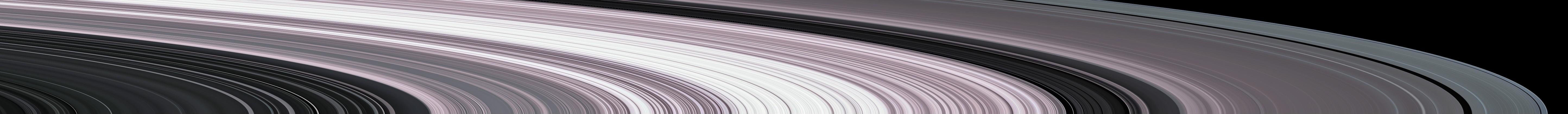

- Gameplay : This is where the fun is had. This scene has the map front and center—a semi-transparent pipe that the “critters” flow through each wave (hence the name Drainage). Contains the Pause Menu subscene.

- Game Over : Simple screen that launches when you run out of lives. The only button redirects to the Main Menu.

- Victory : Same as the Game Over scene, except launches when you pass a predetermined number of levels.

There are three different types of critters, and three different tower types. Each have different characteristics, costs, and speeds. Each tower can be upgraded twice. There are two different choices for tower targeting powers, first critter in range or last.

The pieces of the pipe that the critters pass through were modeled in Blender. The original plan was to model all of the towers and critters in Blender as well, but due to time constraints that plan was cut short, and the default Unity objects were used instead.

GAMEPLAY

[gameplay video coming soon]

I’m disappointed to admit that Drainage isn’t likely to be coming to this website any time soon. There were a whole host of build issues that arose when attempting to package it as a standalone or web-based application, and they aren’t likely to be fixed.

TAKEAWAY

Development got cut short by deadlines, as is always the case with projects build on the clock. The end game plays through smoothly enough, though it is still riddled with bugs that would need to be rooted out in a long testing phase. The foundation that the game is built on isn’t sturdy enough to continue development and eventually ship it out, but the act of building it provided a more than adequate introduction to Unity.

All things considered, I’m satisfied with the end product and am extremely excited to have Unity in my repertoire of tools moving forward. Having a ‘physical’ 3D environment that you can simply attach scripts to will surely prove immensely useful in many future instances. Additionally, creating a GUI in Unity is amazingly simple. Gone are the days of struggling and fiddling with Swing—any project that needs a GUI can be developed as normal with one MonoBehaviour class handling the entire visual setup and IO.

I’ve been interested in making a Fire Emblem-esque turn-based strategy game for quite some time. Maybe it’s finally time to give that one a shot. Who knows—maybe I’ll never get around to this particular project. What I am sure of is that I’m far from done with the Unity Game Engine.

GH